|

An assistant

professor of replicative media in the Institute for Visual and Public

Art, Gilbert Neri has an undergraduate degree from UC-San Diego and

an M.A. from UC-Santa Barbara. He joined CSUMB in the fall of 2001,

drawn by the power of the university’s Vision Statement as well

as VPA’s socially conscious approach to art making. |

VPA Professors Johanna Poethig and Gilbert Neri

|

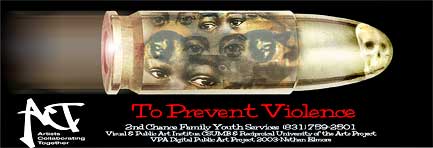

Along

with Johanna Poethig, Gilbert teaches the large-scale digital public

art class. In this class students learn digital art through a content-based,

community collaborative practice. In the 2002-2003 school year, the

class collaborated with the Second Chance Youth Program in Salinas to

develop a series of billboards, signs and posters with anti-gang, anti-youth

violence messages.

Joan Weiner, RUAP coordinator, interviewed Gilbert. |

JW:

What is the objective of the digital art class? Tell me a little about

the principles that shape this class. How does it fit in with the VPA

vision?

GN: The objectives in the large-scale digital mural class are many, but

among the most important are creating public artwork in a true collaboration

with our community partner as well as examining the role of the artist

in the community.

One of the driving principles behind the class is the bridging of longstanding

gaps between the university and the communities for which it exists. Through

RUAP, community relationships are not only established for the particular

project we are working on in a given year, but are also maintained and

allowed a space to grow for future collaborations and other creative projects.

Another of the guiding principles/goals in this class is the investigation

of the role of the artist in community-based projects, and also the role

of authorship in these projects. It allows students, in many ways, to

exercise creativity and also to activate that creativity as a form of

social agency rather than as an outside entity, coming into it with pre-formed

ideas about what matters to this community. This, I think, is one of the

essential threads in the broader weave of VPA. It conceptualizes creative

practice in the broader matrix of culture, history and the impact that

creativity can have in envisioning a future as such. |

JW:

How was the decision made to integrate the class with RUAP? A RUAP community

partner has worked with the VPA 306 class each year – Watsonville

Community School, Monterey County AIDS Project, the Monterey Museum

of Art, Second Chance. VPA 306 is an integral part of RUAP, and in some

ways, the backbone of it. How did this come about? |

|

GN: RUAP was envisioned by Amalia Mesa-Bains and Richard Bains as a way

in which to change the ivory tower position many universities hold around

the nation. RUAP allows us to work with community organizations in a more

substantial way than simply a one-time event. The Reciprocal University

for the Arts Project has successfully created an environment and means

through which the Institutes for Visual and Public Art and Music and Performing

Arts collaborate with the local communities on creative projects.

The large-scale digital mural course addresses the complex process of

creating and exhibiting public art. In this case the artwork is primarily

digitally created, but the underlying tenets of public art issues are

always present. RUAP works in tandem with this class as support and liaison

to our community partner. RUAP establishes the partnership, and then our

class continues the partnership through collaborative public art production. |

JW:

Can you describe the interaction you observe between your students and

the Second Chance youngsters?

GN: Before we meet our community partner members, Johanna Poethig and

I have students read about and discuss the broader social and cultural

issues that might impact our community partner. In other words, we attempt

to build a collective understanding of our own preconceptions, as well

as an understanding that we can bring to the table. It is very necessary

background work needed to express the respect for a group or community

one may not know much about. It is a way of digging deeper into the issues

and details that our community partner might grapple with on a day-to-day

basis, and also give us insights into the value of the work that they

do.

The interaction between our class and the youth from Second Chance was

one that continually evolved. At first, of course, we were all getting

to know one another, and also collectively crafting what we wanted to

do. As a class, we do not dictate what the project will be. This is created

only when the community partner’s members arrive. It gives the youth

a place for their own voice to be heard and allows them to really own

and invest in the project.

So over the year, the relationships we built with the youth grew, and

as confidence grew, so, too, did the process of the project. |

JW:

What do your students get out of the collaboration with community partners?

In what ways did the class challenge the students by having to work collaboratively?

GN: I think each student takes something different away form the class,

especially because we all bring quite different life stories to the table.

I think, though, that one of the challenges that the class poses is to

bring into question the traditional notion of the artist-as-sole-creator.

The project we create belongs to no one and everyone at once. I think

it is a challenge that most of our students meet with enthusiasm.

Another challenge is posed by students having to contact a local business

for exhibition space. This was true of our class last year where we collaborated

with the Monterey Museum of Art. I think the most significant thing here

is that you are really putting yourself in a position where you are an

advocate, community member, artist and collaborator all at once. It is

a generous and vulnerable place to work from, but ultimately very rewarding.

Johanna and I share every part of the process of contacting community

members, organizing meetings, and dealing with the money issues involved

in creating our project. Every part of the process is front and center;

decisions are made by the class and our community partners. So there are

many ways the class offers up collaborative challenges. |

| JW:

How does the experience impact the Second Chance youngsters? Do you see

changes in their attitudes, perceptions, participation level, etc., over

the course of the semester? |

|

GN:

Again, our youth come from such diverse circumstances that it is hard

to tell what impact it might have, but there are some visible changes,

which are always great to see. This year one of our youth went on to record

some hip-hop music and take part in a project called “Transmissions”

which was a sound/art event that took place in Salinas. I think he, most

visibly, has such confidence, and I think he was able to see his creative

work as something that others would engage with.

Two of the three youth from the first semester were incarcerated before

the end of the semester. After they were released, they had no obligation

to return to the class, but did so because they were really into what

we were doing. This was great to see, and they were such a powerful and

guiding force in the way the project developed. |

JW:

If it weren’t for RUAP, how would the class be different? Is having

a community partner essential to the mission of VPA 306?

GN: Definitely. Without RUAP operating as support and liaison to the community,

VPA 306 would be a large-scale digital art class that is probably like

any other digital art class. You cannot teach the creation of public art

in as comprehensive a way without a direct and sustained connection to

the community you are a part of. RUAP allows the class to take on the

creative aspect of the work, but also make visible the often invisible

work it takes to create and maintain community partnerships that are reciprocal

and lasting. |

|